Slides: BCRA_October 2019

pdf: Argentina_BCRA accounting

Buried deep within the monthly balance sheet of the Banco Central de la República Argentina (BCRA) is an arcane accounting entry of crucial import. The entry in question, reported as “Cents Varias,” is more often labelled in IMF documents as Other Items Net (OIN.)

Now, OIN is indeed a misunderstood accounting entry—thus greatly abused. People sometimes think of it as similar to “errors and omissions” reported in the BOP—a measure of our ignorance. This makes it tempting to use OIN as a residual when projecting or interpreting the monetary accounts. But OIN is completely different. Rather, it scoops up balance sheet items that, though not typically pivotal, can still of value in interpreting macro-financial developments. As for Argentina.

Consider the latest BCRA September balance sheet snapshot. Figure 1 shows OIN in local currency on the left and, on the right, BCRA’s net open position (NOP) alongside net foreign assets (NFA) measured in USD. NOP here being the value of foreign currency assets minus liabilities held against nonresident and residents (NFA being that against nonresidents alone.)

To be clear, net equity is a liability on the BCRA balance sheet. But it enters OIN with the opposite sign as it is shifted for analytical purposes to the asset side of the balance sheet. As such, ARS depreciation that would typically cause revaluation of NOP, recording a paper increase in net equity, in fact pushes OIN ever lower—that is more negative. And as previously argued on this blog, these paper gains have been historically converted into local currency as profit transfers, further undermining the currency.

But eyeballing Figure 1, what happened in August? Despite the sharp ARS depreciation, expected to drive net equity higher and OIN negative, instead OIN leaped higher—moving from about -ARS650bn in July to +ARS300bn in September. (Figure 1, left side.) Why? Good question. The right side of Figure 1 provides a clue in presenting USD value of NOP and NFA. While NFA fell sharply on intervention to hold up the currency (from USD47bn to USD29bn) overall NOP fell even further (from USD62bn to USD30bn).

Figure 2 breaks out the NOP further into NFA, net FX claims on the government, and net FX claims on the financial sector. The former is, roughly, familiar reserve assets minus China swap lines. The latter reflects some FX deposits of the financial sector. Meanwhile, net FX claims on the government are the legacy of FX credit provided to the government over years of fiscal dominance. And it is these net FX claims that have fallen most sharply of late, concurrent with ARS depreciation. Indeed, net FX claims fell from USD30bn to only USD10bn.

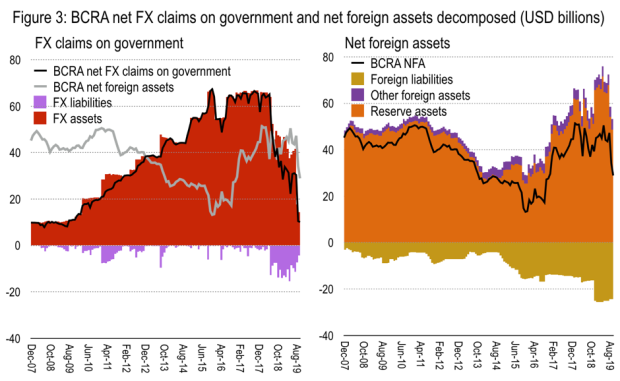

Figure 3 further decomposes net FX claims on the government (left side) and net foreignassets (right.) The left chart in particular shows how FX claims of BCRA—that is, government debt owed to the central bank, denominated in foreign currency—was sharply reduced in August and September. To be precise, these claims fell from USD42bn to USD14bn. Liabilities to the government also fell, so the change in the net position was less pronounced. But clearly, government debt to BCRA fell precipitously in August and September.

So, has the central bank written off government debt? Sadly, no.

Upon careful inspection, it turns out this is not the only time this has happened. Barely visible in Figure 1 is the fact that OIN fell sharply in June 2018 as ARS depreciated, but also increased sharply in July—to be precise, falling from about -ARS620bn in May 2018, to -ARS870bn in June, before rebounding to -ARS420bn. So the imprint of ARS depreciation in the June depreciation was quickly offset. And the 2018 BCRA Financial Statement sheds some light on this episode (see pages 16-17), where it explains how, whereas previously claims on the government were “held to maturity” they decided in late-2017 these would be somehow marked to market.

To be quite honest, the explanation is mostly gibberish to me. But it seems that BCRA decided to apply a more realistic valuation of their holdings of claims on the government. Thus, whereas previously the upward valuation adjustments of claims on government during periods of exchange rate weakness created profit transfers, from last year BCRA instead undertook to mark down cumulated claims on the government at such times of disruption.

Further confirmation of this is available in the BCRA weekly balance sheet reporting. Figure 4. Now, the weekly balance sheet does not have quite the same sectoral and currency breakdown. But it includes a curious memo item from 2019. That is, the weekly balance sheet reports “Net equity” but also that valued “with nontransferable bills at ‘technical value.’” While the former captures the value of BCRA claims on the government “marked to market,” the latter reflects, I guess, the held to maturity value in local currency. And this indeed confirms that BCRA took large losses on their claims on the government coincident with the sharp August depreciation. As such, whereas net equity was recorded at ARS580bn at end-July, it reached -ARS130bn by end-August (recall, this enters with the opposite sign in OIN as it jumps across the balance sheet). In contrast, the “technical value” of these FX claims increased with the exchange rate depreciation, confirming BCRA has indeed written down the value of claims on the government on their balance sheet.

We ought to clear up a few points here—and offer some parenthetical remarks. First, has BCRA “written off” government debt, meaning debt is now actually lower? No. The debt remains unchanged in debt stock numbers. This is simply recognition by BCRA that the government’s liabilities are not worth the paper they are written on. Consider how they have written down USD67 billion in FX claims on the government to USD14bn. That’s an 80% haircut. And bondholders are apparently arguing for a re-profiling of debt. Seriously.

Still, in terms of motives, this revaluation perhaps reflects past frustration that paper gains following ARS depreciations were monetized. Thus, maybe BCRA got ahead of the government by marking down their assets and, by end-August, reporting negative equity. It’s difficult to argue in favor of monetizing negative net equity.

Two more observations. Somewhat visible in Figure 3 (right side) is the extension of swap lines by China during 2014. This was, meanwhile, coincident with increasing BCRA FX claims on the government (left). Thus, in a sense, BCRA appears to have been intermediating funds from the Chinese authorities to the previous government. This clearly helped the previous and more recent government delay adjustment—as did more recent IMF official support. Such lending doesn’t really help. There is a strong case for debt relief on such official support, in my view.

Finally, while the government had previously provided “ring-fenced” deposits at BCRA as part of the IMF program, intended to help shore up international reserves, these have fallen sharply in recent weeks. Figure 5. Following the election result and pressure on the currency, the government has used most of these.

END.

One thought on “Argentina: BCRA accounting and government debt”