Restoring sustainability

The attached presentation from May 2024 derives a general sustainability relation for Argentina based on the consolidated fiscal-monetary-bop relations.

Where the IMF’s traditional financial programming approach was based on an iterative process to achieve sector consistency, today naive fiscal policy and debt sustainability exercises are not integrated with the balance of payments or the overall policy approach.

Iterating between sectors within the sustainability framework reconciles the DSA with the IMF’s traditional approach.

A conversation with David Laidler

A look-back at a distinguished career in macroeconomics

Earlier this year I became, belatedly, acquainted with the work of David Laidler, Emeritus Professor at University of Western Ontario.

Having enjoyed several fascinating interactions with David earlier this year, I thought it might be useful to record one such conversation in the spirit of the age.

Topics include:

- Undergraduate macroeconomics at LSE in the 1950s, interactions with Popper and Robbins;

- Heading to the United States to delay National Service–and ending up at the University of Chicago taking Friedman’s Price Theory course in the same class as Lucas;

- Chancing upon a summer position at the NBER, then in New York, as research assistant to Anna Schwartz on the Monetary History;

- Learning monetary economics from Harry Johnson, not Friedman, at Chicago;

- Despite concentrating on public finance, converting to a monetary economist after being elected to teach the course in his first job at Berkeley;

- Rapidly leaving Berkeley for Essex in 1966 to escape the draft;

- Becoming something of a celebrity in the 1970s in the UK as inflation and monetarism came to dominate the public discourse;

- His near-brush with Thatcherism, but ultimately staying in Canada (where he Laidler moved in the 1970s);

- A life-long interest in the history of thought, and it’s continuing, vital importance;

As can be seen, we reference some of our previous interactions.

Unfortunately, due to some technical issues on my side, some of this conversation is punctuated. But I hope this does not spoil what I hope is a pleasant interaction with someone who indeed meets the description of “gentleman and scholar.”

(Don’t fear) the repo

Inside the New Keynesian black box

United Kingdom Stand-By Arrangement 1976

A little bit of history on the last occasion that the UK faced a challenge similar to today–the IMF’s Stand-By Arrangement document from 1976.

It’s interesting to note the similarities between then and now.

An incomplete list would include: oil shock, twin deficits, rapid money growth, labour unrest, political dysfunction, high inflation and rapid wage growth…

Also refreshing here is the quality of the IMF’s analysis compared to today. And since these documents were not published, as they are today, Fund staff could be more pointed in their assessment of the macroeconomic failings of the UK authorities.

There are also margin notes by Fund management later in the document.

Ethics and corruption at the International Monetary Fund

The findings of an external report on governance failings at the Fund, by a panel led by Jens Weidmann, was quietly buried before the summer—presumably in the hope that no-one would notice. Weidmann’s report was deeply unsettling for the international monetary system. And the attempt to cover it up indicative of the depth of corruption and misconduct by Fund management and staff—on Georgieva’s watch.

THE APPOINTMENT OF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) two years ago cast uncomfortable light on the stewardship of the international monetary system. It was soon alleged that Georgieva, in her previous position across 19th Street, “told staff at the World Bank to amend rankings [in several editions of the Bank’s Doing Business Report (DBR)] to China’s benefit.”

The possibility that the Fund’s new Managing Director might be willing to cook analytical results to favour some member country-or-other could fatally undermine the necessary impartiality of the IMF. But after eight meetings of the Fund’s Executive Board, Georgieva survived an internal probe—unlike the DBR, which was hastily discontinued just over a year ago.

This did not completely end the matter, however.

In clearing Georgieva, the Board suggested it might be useful to “consider possible additional steps to ensure the strength of institutional safeguards” in the areas of “governance and integrity in the data, research, and operations of the IMF… [as well as] … channels for complaint, dissent, and accountability.”

This triggered two internal working groups at the Fund earlier this year under the rubric of an Institutional Safeguards Review.

The first was a staff Working Group on Data and Analysis Integrity, “established to assess the possible need for changes in processes safeguarding the integrity of data and analysis at the Fund.”

The second a Working Group on Internal Governance and Staff Voice—a body that in turn recommended the establishment of an External Panel of Experts “to conduct an independent, strategic review” of the Fund’s Dispute Resolution System (DRS) and “the framework for addressing complaints applicable to the Managing Director and Board Officials.”

Accordingly, an external Panel, led by former Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann, was appointed in February with the following terms of reference:

The Panel’s review will benchmark the Fund’s DRS against comparators (i.e., other international organizations) and best practices, including from the corporate sector, where relevant, in providing stakeholders with fair and impartial channels of recourse for dissent without fear of reprisal or retaliation and in facilitating resolution of disputes in a timely manner. The review should identify strengths and key gaps of the Fund’s DRS. The review should cover whistleblower protections and mechanisms for receiving such complaints.

Against this background, by late-June two documents were published by the IMF to finally resolve the controversy surrounding Georgieva’s appointment.

The first was a Report on Data and Analysis Integrity, prepared by the aforementioned internalworking group led by Fund staff; the second a Report on the Review of the IMF’s Dispute Resolution System, from the external panel led by Jens Weidmann.

It is remarkable that the findings of the latter Panel in particular, which we take up here, passed largely unnoticed by the world’s media—both due to the profiles of its esteemed members involved and the nature of the revelations contained therein.

Perhaps one reason for such oversight is that the Report itself has been—presumably deliberately—obscured. It was silently appended to the internal working group’s report on data and analytical integrity—and not referenced in the abstract of the document, making it almost impossible to find.

Given the lengths taken to conceal the Weidmann Panel Report its findings ought to be more widely appreciated.

Weidmann’s findings

IT IS WORTH recalling that the Weidmann Panel’s terms of reference restricts their orbit to dispute resolution and whistleblower protections. This makes sense in light of irregularities alleged in the construct of the World Bank’s DBR, after which “internal reports raised ethical matters, including the conduct of former Board officials as well as current and/or former Bank staff…”

Should an individual inside the Fund raise concerns about the ethical conduct of management or other staff, are the internal processes for dealing with such complaints sufficiently robust?

That said, it is somewhat ironic, though worth noting up front, that the allegations against Georgieva are relatively slight when lined up against the rogue gallery of the three most recent Managing Directors—who, in reverse chronological order, have been convicted of negligence in a prior professional life; resigned on the job after allegations of sexual assault in a New York hotel room, later settled out of court; and found guilty of embezzlement in a later position of power.

Then again, allegations against Georgieva are perhaps more serious in that they represent the type of soft corruption most available to the average member of Fund management or staff—the sort of reciprocal engagement and kleptocracy common amongst bureaucracies closed to outside scrutiny.

The Weidmann Panel began with a survey to get a sense of: (i) “staff’s perception of the Fund’s dispute resolution system from the perspective of those for whom the system was created;” as well as (ii) the bullying, intimidation and sexual harassment witnessed or experienced by staff over the past 5 years.

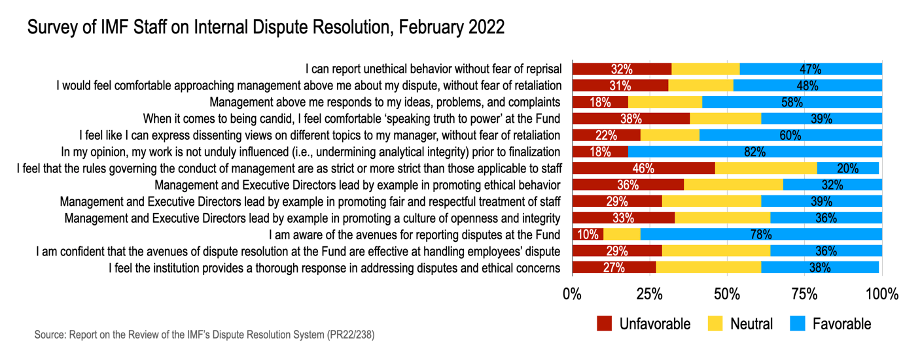

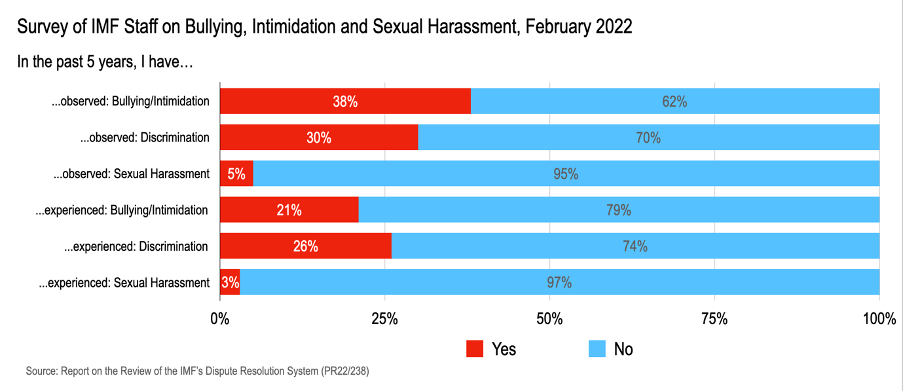

These results are shown in the next two charts. The first summarizes the Board, management and staff perceptions relating to dispute resolution (taken from Table 3 in the Weidmann Panel Report) the second that regarding bullying, intimidation, and sexual harassment (Table 4).

Amongst other findings, the dispute resolution survey reveals:

- A high turnout, with nearly 1,600 responses (40% of staff) of which about 1,400 were complete and 200 partially complete—with a fairly representative sample across grades and departments;

- About one-third (32%) of “respondents fear retaliation and do not trust the [dispute resolution] system;”

- Nearly half (46%) saw management as held to a lower standard of accountability then staff;

- “Almost two-fifths [36%] … did not feel that Management leads from the top and is held to a lower standard of accountability;”

- And nearly one-fifth (18%) believe their work is unduly influenced prior to publication.

As for “bullying/intimidation, discrimination, and sexual harassment:”

- Nearly one-fifth of staff had personally experienced bulling/intimidation (21%) and about one-quarter (26%) discrimination over the past 5-years;

- Alternatively, during this time nearly two-fifths (38%) of staff had observed billing/intimidation and one-third (30%) discrimination;

- About one-in-twenty Fund staff members had observed, and 3% personally experienced, sexual harassment over the past 5-years;

- However, “only a third of respondents reported incidents of bullying or intimidation, discrimination, and sexual harassment;”

- Meanwhile, staff did not report incidents because they “did not believe appropriate corrective action would be taken or that the situation would not be resolved in a fair or impartial manner.”

- “Additionally, staff feared retaliation for reporting the allegations, particularly from managers.”

But the Panel went further.

They also interviewed current and former employees while providing a “confidential and external email access” to gain further insights. And this uncovered, again amongst other things, the following:

- The culture of the Fund does not encourage employees to speak up against ethical transgressions or harassment;

- “All of the persons who communicated with the Panel and had used the DRS complained that they had suffered retaliation, felt they were not adequately protected from retaliation by the Fund, and they stated that the people responsible for retaliatory acts were not held accountable;”

- When dispute arbitration happens, it takes too long—“one or both parties to the dispute might have left the Fund by the time the matter was resolved”—while such disputes involved a “high personal toll, as well as the financial cost of hiring legal representation;”

- For some who raised concerns the Human Resource Department “refused to disclose requested documents to them either before or as part of their request for administrative review;”

- In addition, “several employees who spoke to the Panel… [believe there] are currently inadequate or unclear safeguards or mechanisms in place for dealing with issues of undue influence or alleged violations of data integrity;”

- Moreover, “all of the [16] employees who spoke up about the pressure placed on them to alter their reports unjustifiably were allegedly subjected to retaliation and reprisals.”

The Weidmann Panel was careful to point out that the information gathered through interviews and emails aligned closely with the survey results, providing “credible grounds for the conclusion that the perceptions of these stakeholders” was not just an aberration or selection bias.

In short: the report uncovered a culture inside the IMF of unethical conduct and reprisals against those who tried to challenge such behaviour. No wonder the results of the Weidmann Panel, announced with such fanfare as the year began, was quietly buried on the Fund website.

But the very act of burying these uncomfortable results only echoes the very act of soft corruption of which Georgieva was originally accused—underlining that she was pushing on an open door when she crossed 19th Street.

END.

Argentina and the Fund: From Tragedy to Farce

“If you owe your bank manager a thousand pounds, you are at his mercy. If you owe him a million pounds, he is at your mercy.” An old saying, the modern incarnation of which is often attributed to Lord Keynes.

Argentina’s revised program under an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) with the IMF was approved late last month. The associated Staff Report was dropped onto the imf.org webpage with minimal fanfare. It wasn’t posted to the main landing page, as with most Fund documents, only to the Argentina country page. This gives a hint at the internal enthusiasm for the document itself.

Roughly speaking, the new program rolls over the previous Stand-By Arrangement (SBA)—pushing back the repayment period to between 2026 and 2034 while returning to Argentina interest they paid in recent years.

What can be said analytically about this revised document?

Well, at one level there is much to be said. And some of what ought to be said we will say here.

Continue reading “Argentina and the Fund: From Tragedy to Farce”